Welcome to the

Info/Demo page for MATH 337,

Numerical Differential Equations!

When creating this page, I had in mind the following goals:

1. To describe the background

you will need to succeed in this course;

2. To describe what the course

will cover;

and

3. To demonstrate the level of

complexity of the problems that the students who had taken this course

were able to solve.

The first two goals are covered in the Info part of this page. To skip

that part and go directly to the Demos, which address the third goal,

click here.

Info

Background:

You will need to know the basic Calculus (especially

the Taylor series) and Linear Algebra (especially the eigenvalues). Any

knowledge of the ordinary differential equations (ODEs) beyond what is

commonly covered in Calculus, as well as familiarity with partial

differential equations (PDEs) and Fourier transform, will be

beneficial, but not critical

for succeeding in this course.

The other important ingredient is your willingness to program, although no

programming proficiency on your part is assumed. After all, the way to

solve most real-world problems is to program them into codes! The

programming language of the course is Matlab.

Course outline:

Part

I of the course will describe methods of solution of

initial-value problems for ODEs. This class of problems

arises when a scientists studies the development of some process in

time. Examples include evolution of the population of a biological

species, dynamics of a laser beam, motion of a charged particle in

electric and magnetic fields, etc.

Part I also lays down the mathematical background on which the other

material of this course will rest. Namely, the students learn how to

write numerical schemes whose solutions are guaranteed to closely approximate

the analytical solutions of the respective ODEs. This is quite

remarkable, considering that one usually does not know what that

analytical solution is!

Part II

will describe methods of solution of boundary values problems for ODEs.

Examples of this class of problems include finding the shape of a

loaded beam, a stationary temperature or heat flow distribution in a

reservoir, etc.

Finally, in Part III the students will

learn how to solve initial-value problems for partial differential

equations. This class of problems is similar to that studied in Part I,

with the modification being that now the process in question

develops differently in different regions of the space! The

applications include the heat transfer, traffic flow, propagation of

electric pulses in media with complex properties, etc.

The course does not specifically cover (due to the

lack of time) methods for modeling wave propagation. However, the

mathematical background that the course provides is amply sufficient

for the students to learn those methods on their own.

For the Final

Project, the students are offered a list of topics from

which they select the one they are most interested in. For

example, learning and applying one of the numerical methods to a wave

propagation problem may be one of such topics. As another example, the

second demo on this page was created by a student as his final project.

Students are also welcome to suggest their own problems they would like

to solve numerically.

For more

information, visit the main

page of this course.

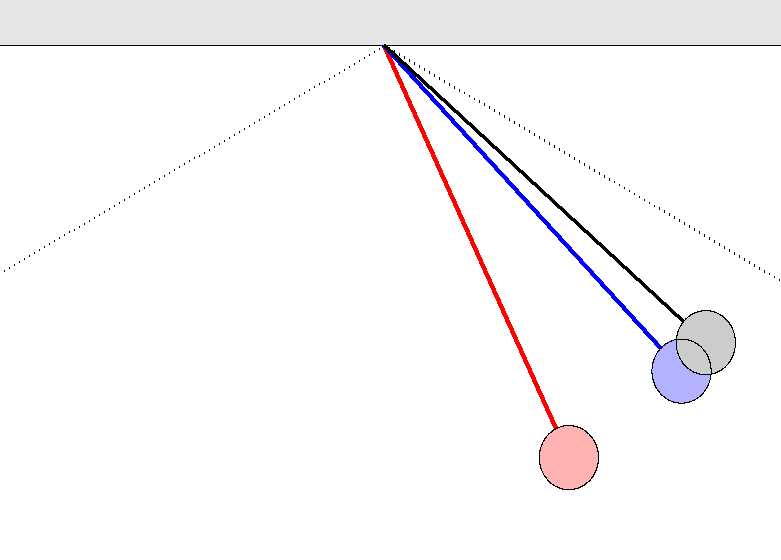

The first

Demo illustrates that the knowledge of properties of a numerical

method is sometimes critical for the method's success, when it is

applied to a specific problem.

The movie below shows the evolution of a slightly damped

pendulum when computed by:

(a) a 2nd-order accurate modified Euler method and

(b) a 1st-order accurate symplectic Euler method.

The color coding of the penduli is:

Exact solution:

Gray

Modified Euler

method: Pink

Symplectic Euler method:

Blue.

The dotted lines on the sides are the guides for the eye: They show the

maximum elevation of the top point of the pendulum without damping.

Click on the picture on the left to watch the movie of these penduli.

The movie size is 2.7 MB.

Usually, 2nd-order methods are more accurate than 1st-order ones. In

particular, the modified Euler method is widely used due to its

simplicity and relatively good accuracy. However, when applied to a

certain class of problems, this method can lead to totally wrong results.

Namely, note two things in the movie:

* The (supposedly more accurate) 2nd-order numerical solution

deviates farther from the exact solution than the 1st-order numerical

solution.

* The 2nd-order solution even gives qualitatively wrong information: It

shows that the amplitude of the pendulum slowly increases, whereas that

amplitude found from the exact solution slowly decreases!

Symplectic methods, to which the 1st-order method used above belongs,

are a hot topic both in mathematics and in applications. For example,

such methods are widely used in computer animation. Upon taking this

course, the students will learn the reason that causes symplectic

methods to outperform non-symplectic ones.

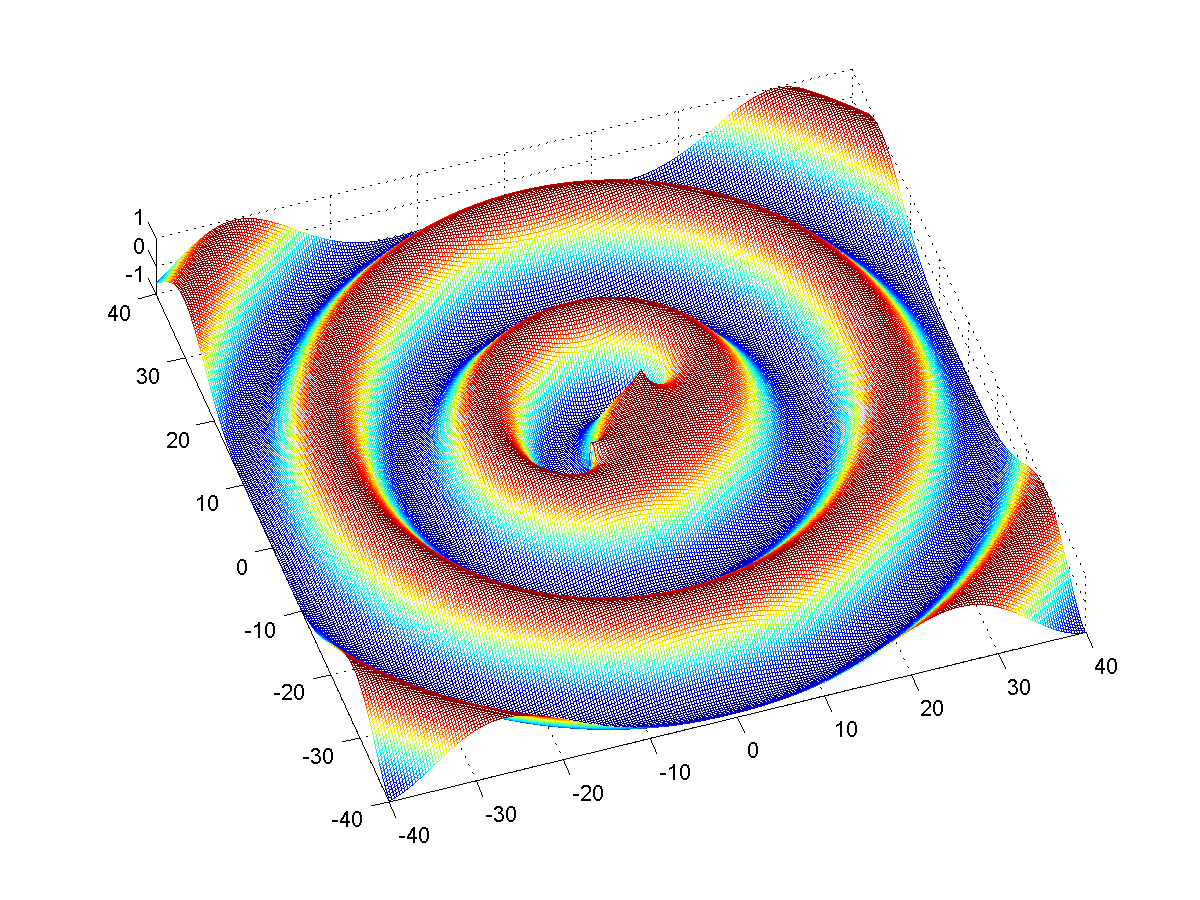

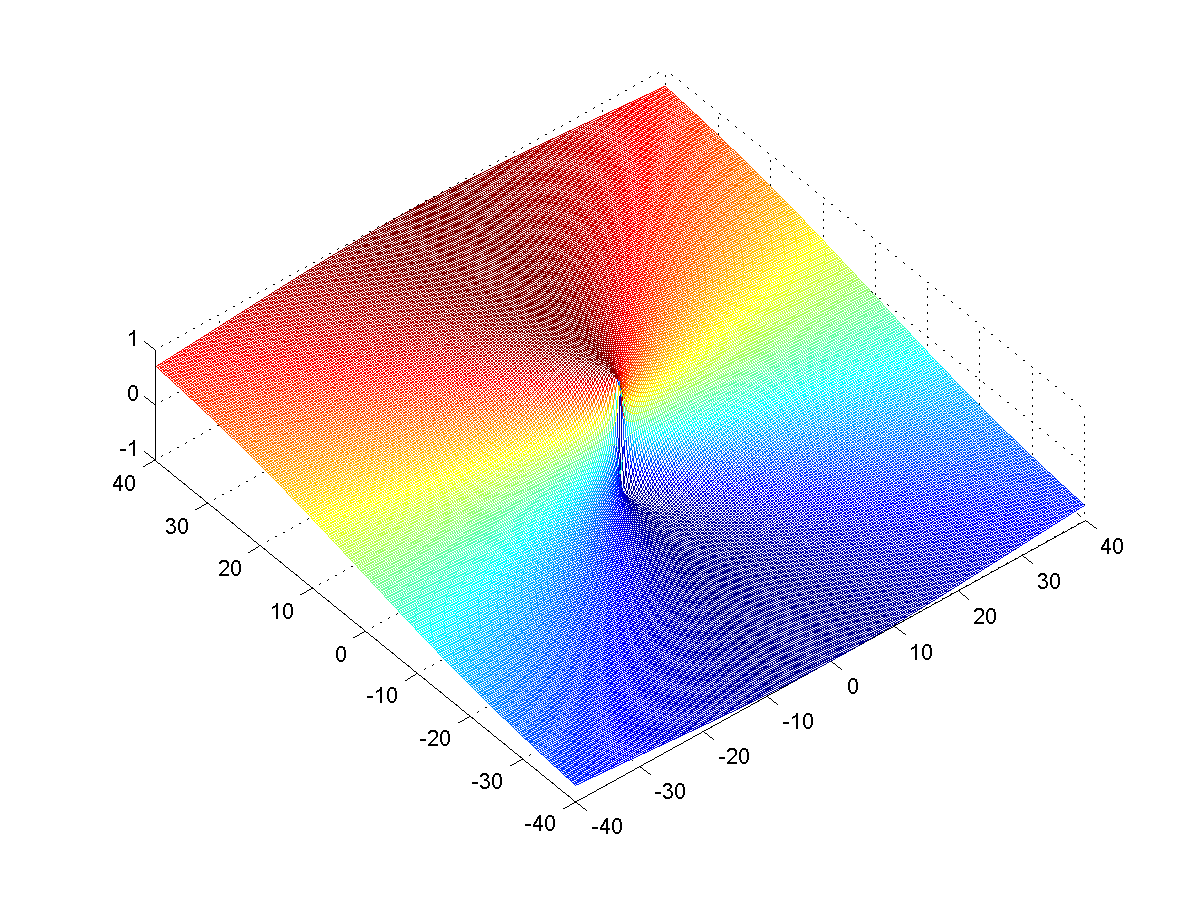

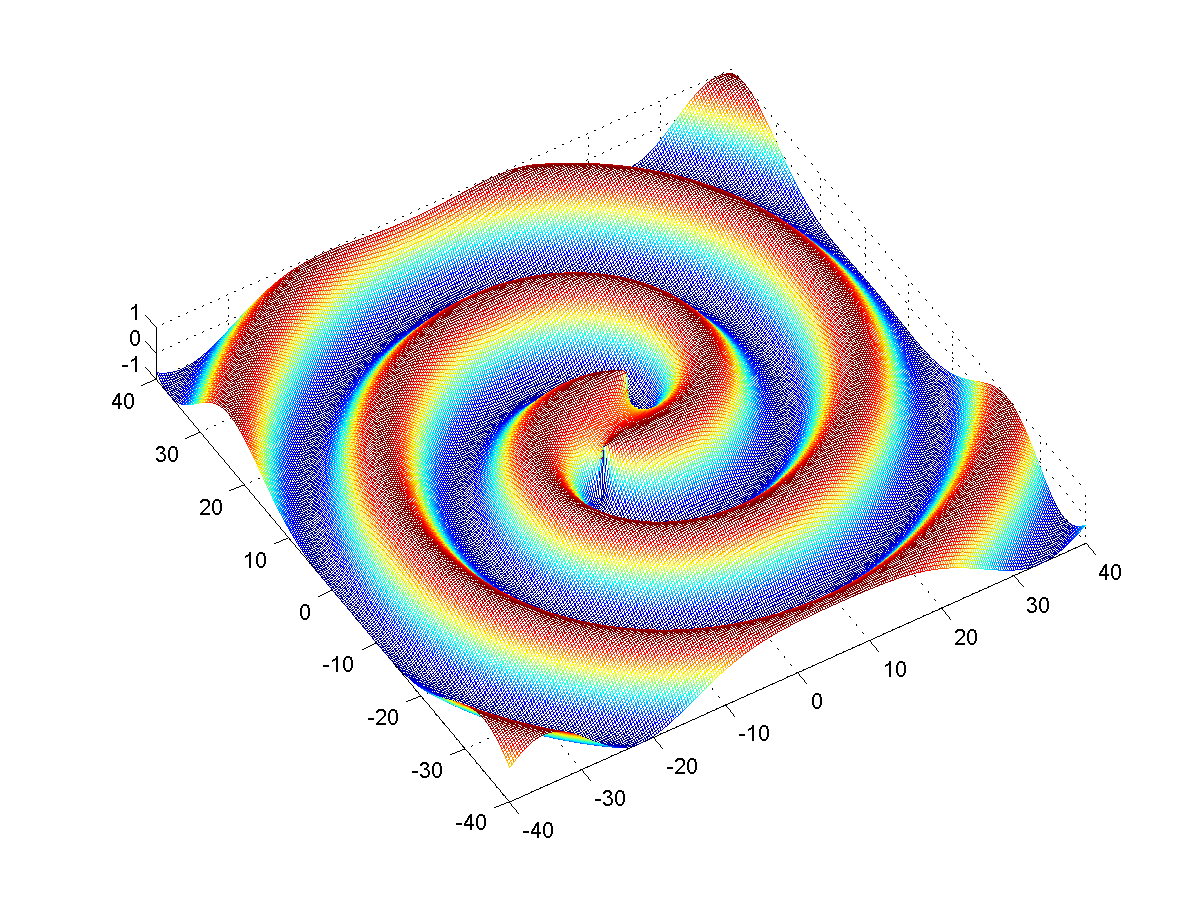

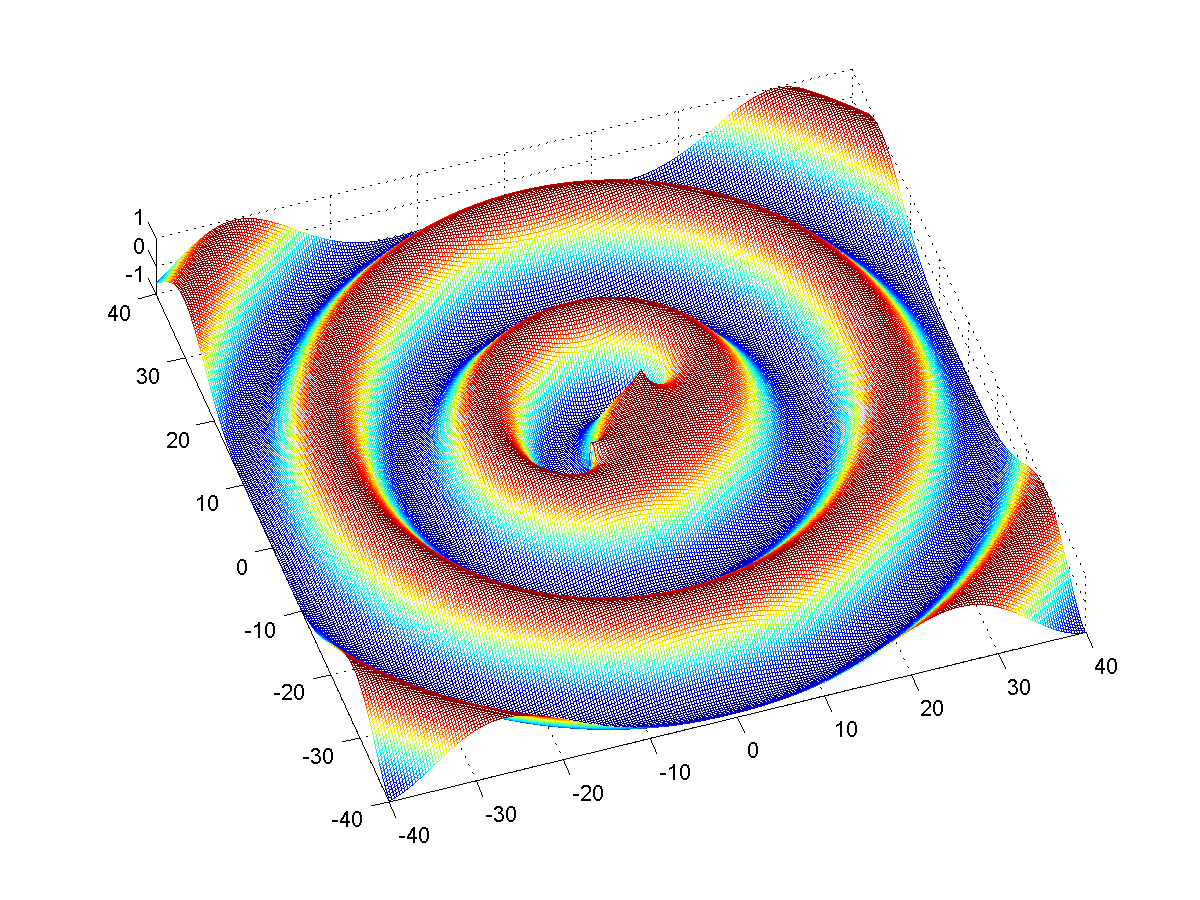

The movies shown in the second Demo

were created by Mr. Evan Flath, who took MATH 238 (a previous name for

MATH 337) in the Spring 2005.

Evan wrote a code that solves the following partial differential

equation in 2 spatial dimensions:

Even with modern computers, solution of PDEs in more than one spatial

dimensions may be quite time-consuming. Therefore, the course

emphasizes time-efficient

methods for such problems. Evan implemented one of such methods in his

code.

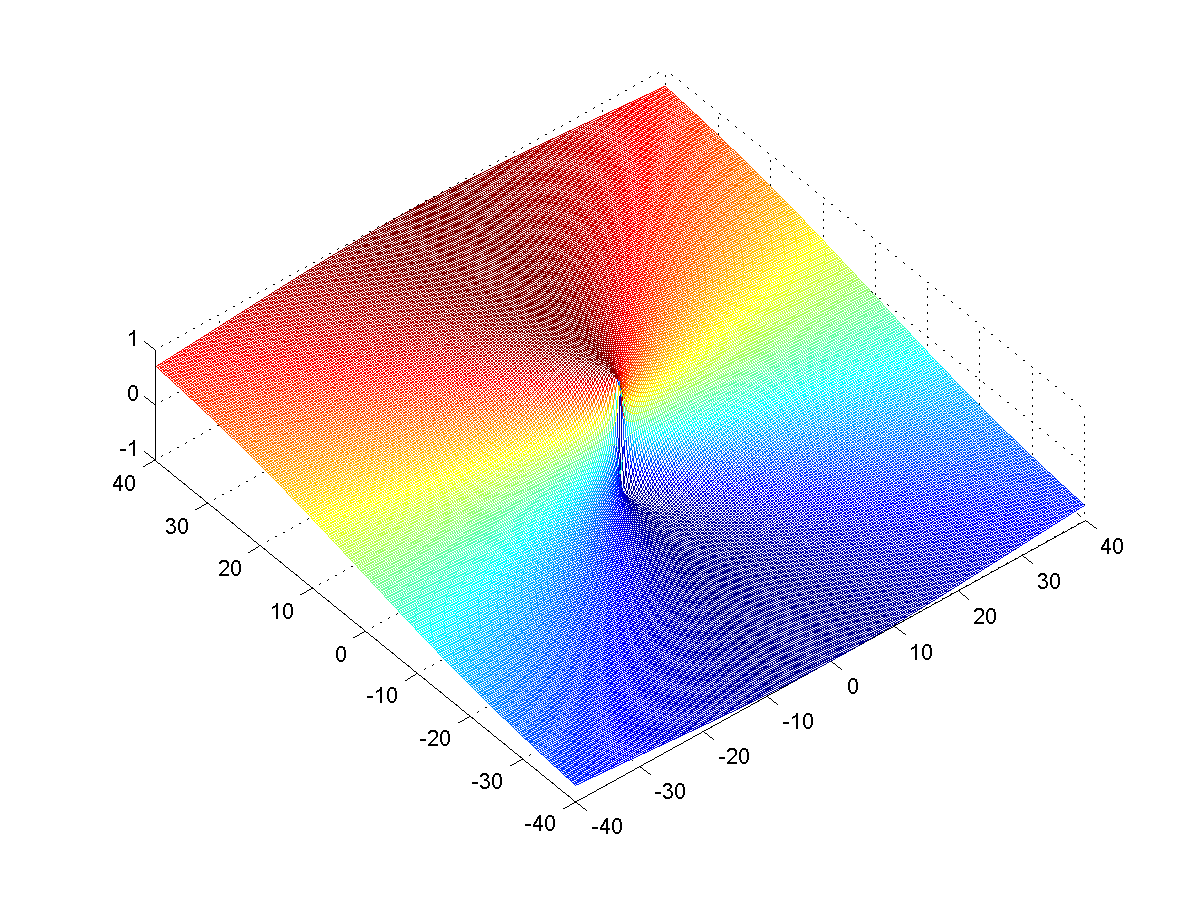

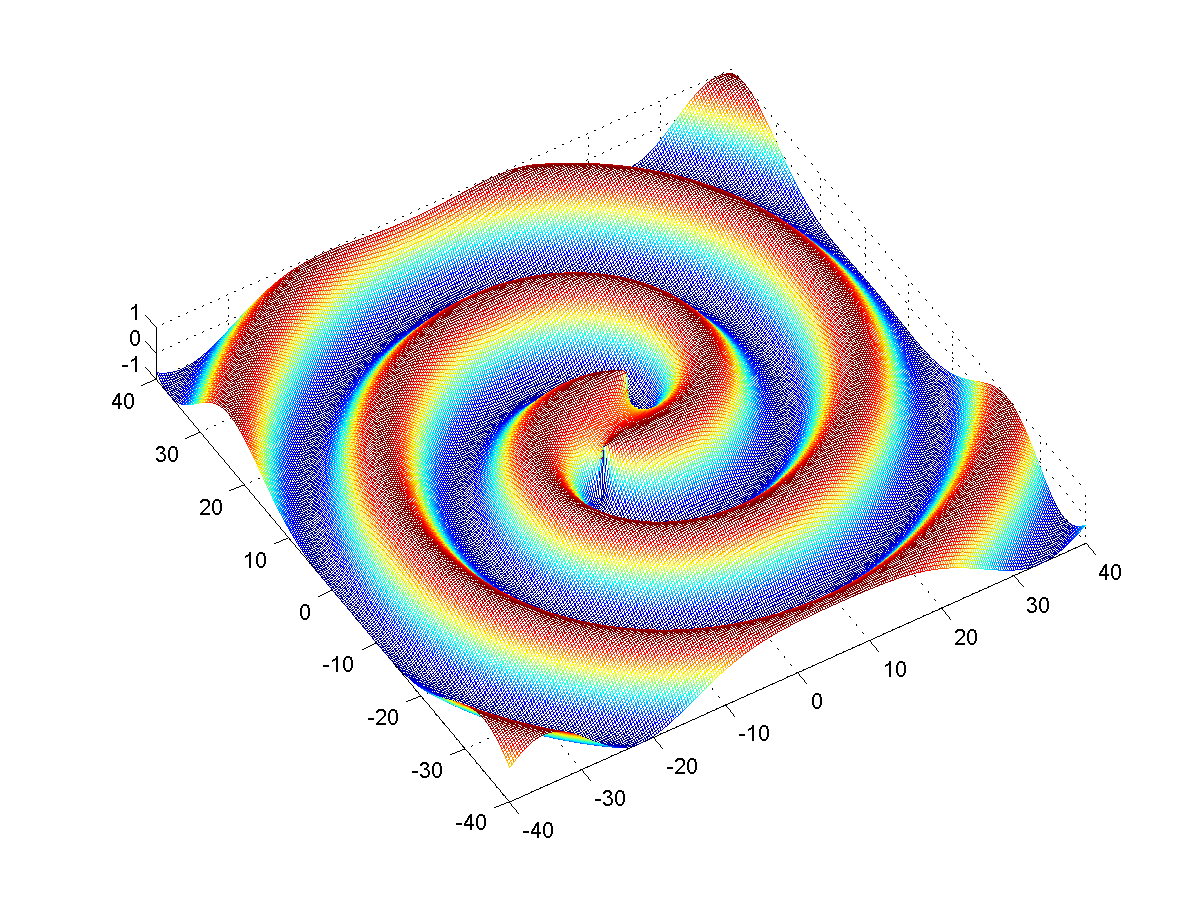

The above equation, known

as the complex Ginzburg-Landau equation, has been found to describe a

great variety of phenomena in physics, chemistry, and biology. Its

particular realization shown here describes the growth of a thin film

at the interface of two crystalline materials (see a paper by I.

Aranson et al, Phys.Rev.Lett. 80,

1770 (1998) for more details). The height of the film is modeled by the

argument of the complex-valued solution of the equation.

The movies depict

three (out of many more) scenarios of the film growth.

The first

movie shows the formation of a spiral out of a so-called screw

dislocation in the original film.

The second movie shows the

evolution of two spirals of the same orientation, whose centers have

drifted close to one another.

The third movie shows a

similar evolution in the case when the orientation of the spirals are

opposite.

To watch the movies, click on the corresponding pictures below. You may

need version 7 or later of QuickTime Player, which you can download for

free from the web.

Note

that the movies show contour plots of both the argument and the modulus

of the solution. As mentioned above, the argument models the film's

height, while the modulus has no independent physical meaning and is

shown only for completeness.

Initial condition:

Screw dislocation (no spirals).

Initial condition:

Two spirals of equal orientation.

Initial condition:

Two spirals of

opposite orientation.

You might have noticed that the solution acquires with time a somewhat

square shape. This is the effect of the boundaries of the square

domain.

Back to the main page of MATH 337